To catch up on the story to date, you can view the archive here.

Between eighth grade and my sophomore year of high school was my phantom year. I wasn’t in public school, I wasn’t in private. Instead, I mostly sat at home and read books. This year corresponded with my 14th birthday, and with my introduction to Game-Maker. It was a year of untempered productivity.

I’ve talked about my early character-focused design. One of my early sources of characters was my former grade and middle school associates. After school or on weekends, they would come by to play videogames; I would drag them to the computer and show them what I was up to.

I think my games mostly puzzled them. They were sort of impressed that the games existed, but they didn’t much understand computers and were mystified by my subject matter and design choices. Inevitably, their minds would wander. They would ask me, could I make a game resembling this other game that they liked? Sure, maybe. I’d try. Could I put them in the game? Well… okay.

At that time, the big thing in my social circle (if that’s the term) was Japanese RPGs — Dragon Warrior, Phantasy Star — and PC strategy games like Star Control. They were also big into arcade brawlers and forced-perspective shooters. None of these genres was a match with Game-Maker, but I did what I could. Often, that wasn’t much.

As the games were requests, I had little ego attachment. I threw them together out of available materials, as fast as I could. I based most of the characters on a standard template, tweaked a bit to resemble my clients. Background and other sprite elements, I borrowed from sample libraries and my own past games. As I churned out the requests, gradually I built up a sort of shared resource pool. Between those resources and some recurring themes, such as Groucho Marx, most of these other-insertion games feel very similar.

If I noticed the repetition, then I didn’t care; I had a job to do. It barely mattered if the games were playable, since they weren’t meant for me. If I could work in some clever references and then finish the project, I was satisfied. And then, on to the next request.

Distribution opened up another problem. As I said, I felt no attachment to the games. Although I felt obliged to release them, I didn’t want to mix this work for hire (as it effectively was) with my personal projects. I therefore devised a sub-label, Don’Pan Software, to aid in distancing myself.

I made no secret of the relationship between the two labels; it was just a mental thing. If it’s no good, don’t panic. It’s not supposed to matter. On this side of the line, you don’t have to care.

There are a few distinct eras and subcategories of insertion games. Right now I’ll just detail the first one, as they have more in common with each other than the rest of the games.

The requests started early. After A-J’s Quest, I think that Cireneg’s Rings may be my second game. It’s hard to be sure, but the more I consider it the likelier it feels. It would have to be early for me to tackle a project like this.

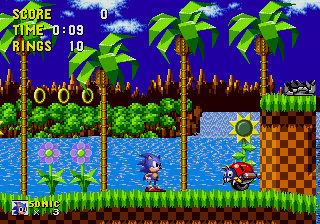

Cireneg’s Rings is an RPG in the tradition of Dragon Warrior, including a generic medieval setting, an evil overlord with a princess in captivity, sprawling towns hiding opaque yet important secrets, and a very slow-moving character.

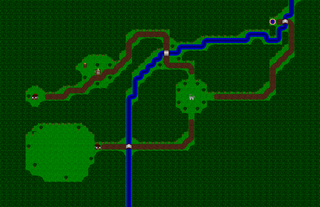

There are a few subversions. You know the convention, popularized by Dragon Warrior, where exiting a city reduces it to the size of a single tile on the world map? The idea is that the journey between points of interest is heavily abstracted — both visually, in the representation of scale, and mechanically, in the random battles that represent personal trials and learning experiences on one’s journeys. In later JRPGs, the convention just becomes a convention: towns grow tiny, while a huge character walks around the map.

So I decided to play with that; whenever you leave a town, the game halts for a moment while your character erupts to an enormous size. This enormous character is then used to tromp the countryside between towns.

Other curiosities include the large “Groucho Rock” formation on the world map, a large healing sauna in each town, and — in early versions — lots and lots of nudity. That’s mostly gone now, though there may be a couple of incidental flashes hidden away. Even without the nudity, most of the townspeople are deliberately wonky. They stand in place and stomp or wave their arms, as townspeople do in games like this — except more so.

If any of this sounds clever, it’s more than offset by the inanity. The game, for instance, is filled with useless items such as armor, which often comes at a steep price. This is not so much commentary as an oversight; Game-Maker provides no way to raise or lower a character’s defenses, and yet I had to include the armor shop. Why? Because this was an RPG. Were I more astute, I could have turned the fact into a gag about in-game financing and genre conventions.

That is, I could have if Game-Maker if Game-Maker supported text overlays — which it didn’t, which probably should have given me pause before I attempted an RPG. Later on the engine got support for interstitial text and animation between levels. Although that made the premise a little clearer, it still left the player to wander aimlessly.

Not that it would have mattered, as at this point I had little concept of how to pace or structure a game. Even if you know precisely where to go and what to do, the smallest of tasks can take forever and the most important events can pass without a hint that something happened. There is no comprehensible flow from place to place, and no build-up or release of tension.

Just to make the continuity even stranger is my failure to account for Game-Maker’s lack of event flags or counter resets, meaning that in theory the player can re-enter a dungeon and collect ten copies of a priceless artifact, or continually leave and enter an area to collect a key or health upgrade. It’s kind of a mess.

On the plus side, Cireneg’s Rings is probably one of the biggest games designed with Game-Maker. I learned early what the game industry in general would take another ten years to figure out: if you can’t do quality, you can always make up for it with scale.

The moment I finished my first RPG, I turned that experience around and attempted another. Whereas Cireneg’s Rings was my take on Dragon Warrior, Linear Volume was a direct rip-off of Phantasy Star II — as close as I could manage.

When it came out, Phantasy Star II was in the range of $80-90 — and this was in 1980s money — so as big an impression as the game made on me, I never had my own copy. Instead, I borrowed the game for perhaps two years from a middle school associate. He was a year ahead of me and I didn’t know him all that well, but we had similar taste in games.

Around the time that I finally returned his game, I decided to make him a sort of thank-you gift. I whipped up a bad copy of the Motavian and Dezolian overworlds, and arbitrarily seeded them with towns and dungeons. I also designed an in-game intro, where a Winthrop Ramblers school bus disappears into a vortex and my acquaintance emerges into, essentially, the world of Phantasy Star II — albeit a version populated with Groucho noses, pickles, and toenail clippers.

When I told him what I was up to, my associate suggested a title and then asked if I meant to distribute the game commercially. If so, he insisted that I change the character’s likeness. This discussion sent a few wheels spinning, and led me to go back and produce a sanitized version of Cireneg’s Rings.

Previously I had given little thought to privacy or social delicacy. From here on, I had a sort of pattern for such games: one edition for the associate in question, and an edited draft for mass consumption. Any personal or gratuitously naughty elements went in the trash, to be replaced with random whimsy. That extra step gave the public editions more care and polish, which easily made them the definitive versions. It also made me feel less awkward about the games.

Around the time that I was wrapping up this project, a fellow who had played Cireneg’s Rings asked that I place him in a space adventure modeled in the vein of Star Trek. At the time I was only slightly familiar with The Next Generation, but a bit more cultured in space shooters and strategy games — in particular Toys for Bob’s Star Control.

Accolade’s Genesis port was another large and expensive cartridge that I had borrowed — twice the size of and possibly even more expensive than Phantasy Star II. It also loomed large in my creative mind, as the game was so darned strange. The cartridge was unlicensed, which meant the molding and the packaging were non-standard, and the actual game design was like nothing seen on a console at that time. Of especial note were the digitized sound effects, so uncommon at the time yet so easily implemented in Game-Maker.

After two wonky RPGs I was eager to try something different, so I set about designing a wonky shooter-adventure — with strong RPG trappings, mind you.

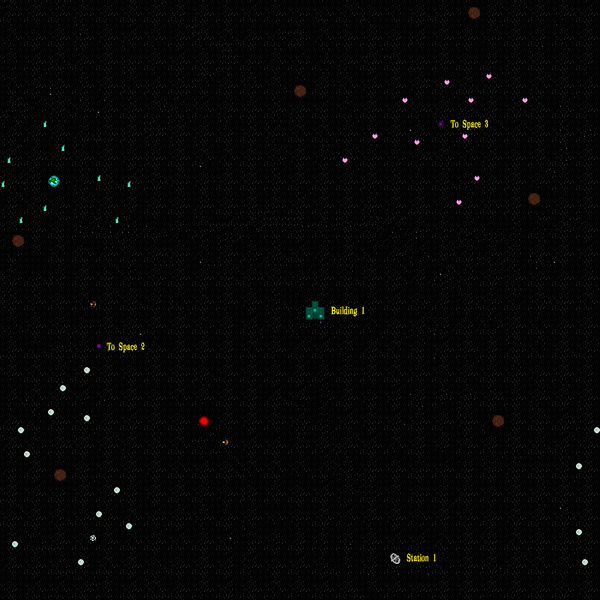

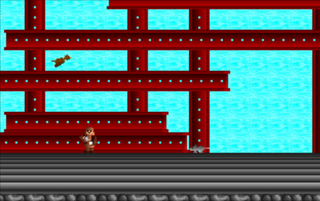

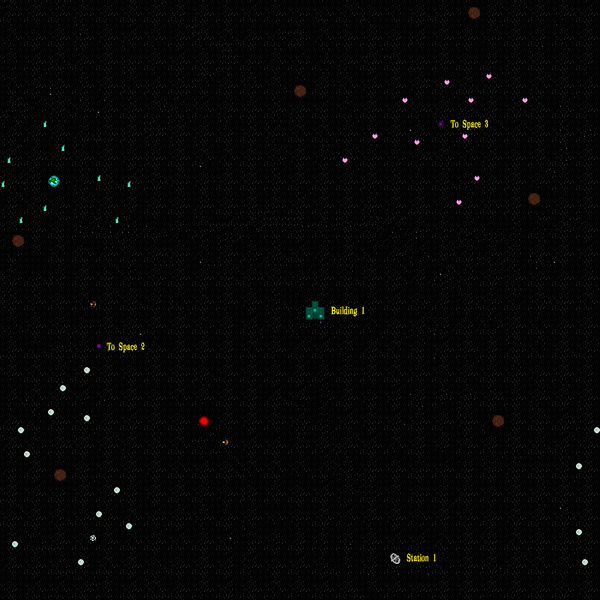

Ultimately, Explorer Jacko was only a slight departure from my earlier games. The way I figured, space would be the overworld — and space would be modeled on the melee mode of Star Control. This didn’t quite work out, but if one is charitable then the space levels might seem like a large-scale version of SpaceWar!, littered with almost pixel-for-pixel copies of some of the more interesting Star Control vessels.

Being space, the overworld is very difficult to navigate. If you putter around long enough, you may come across towns or dungeons — or, if you will, space stations and derelict colonies. Deep Space 9 was the brand new thing in syndication; although I barely watched the show, that was probably an influence. Aside from serving as store fronts, the stations also contained holodecks that allowed for more adolescent mischief.

The player could also disembark at colonies to wander around on foot, shoot monsters, and collect important items. There was little real reason to do this except in pursuit of the game’s very simple, and distressingly imperialist, story. Hidden away in a dungeon, somewhere in space, is the passport that you need to land on a certain planet. Find the passport, then land on the planet. Bingo; you’re done.

The game’s entire challenge comes from the difficulty in finding one’s way, keeping track of where one has been, and in the severely overpowered ships and monsters that the player faces. In order to explore sufficiently to figure out what one is doing, one must destroy countless little monsters to rack up the money to upgrade both the ship and the character’s equipment.

Although the game is a failure in most respects, Jacko in a sense does more successfully follow the JRPG formula than its predecessors. It’s also a sort of interesting mix of play styles, with the constant cycle between a space shooter and an adventure exploration game. The game’s beginning, although poorly implemented, is also curious; the player starts by breaking out of a jail cell, and for a while has no direct means of attack or defense — just some time delayed explosives. Eventually the player finds a ship and, with luck, limps to a nearby space station for help.

Designed better, that might have been a dynamic teaser to draw the player into the game’s action while slowly introducing its concepts. As implemented, it just confuses the player with one irrelevant obstacle after another. Hey, live and learn.

I certainly never tried another RPG, though I had far more strange decisions to come.

The story continues in Part Five…