To catch up on the story to date, you can read the first two parts here and here.

So some of my characters, I spun out of existing projects. Others came about from that web of interests and in-jokes that brought about my Andrew-Jonathan strip in the first place. These characters are built of wholly abstract materials, which makes it all the harder to justify them in design terms.

It would be one thing to base a game on abstract concepts. That’s probably an ideal place to begin, actually; to take vague notions from life and to see how best to communicate those ideas through a framework of cause and effect. You only seldom see this approach; when you do, as in games like Passage or D2, or even Pac-Man, you end up with highly expressive, meaningful content.

To base a game not on concepts, but things — well, you’re always starting on the wrong foot. This is why there are so few excellent licensed games, and why genres and long-standing series tend to devolve into meaningless variations on a form. It’s why tech demos, although fascinating on a level, make such empty and tawdry exercises.

This may be why so few developers have made real use of the Nintendo Wii. Nintendo boiled some brilliant and progressive concepts down to a thing, which developers proceeded to use as a thing rather than explore for the concepts that it represented.

So it’s hard enough to build a game out of an established character. Imagine if that character itself is uncertain. Instead of A-J Bear to draw from, with all his built-in thematic trappings and influences and continuity, you have the vague idea of a hedgehog who is very, very British. Offhand you can throw together a few lazy pitches, but what are you basing those pitches on? Cultural preconceptions? Handy iconography? Are you going to just stop there, or are you going to examine those preconceptions and break down that iconography into something practical and representational?

Think that’s easy? How about a game based on a funny name combined with a meaningless catch phrase? Whoever the character is, this is his name and these are the words that he spouts whenever possible.

Though I’m certain meaningful projects have begun with less material, some tasks were too much even for the slapdash methodology and low artistic standards of my youth.

Considering its origins, Sign of the Hedgehog turned out pretty well. From its title you may ascertain my thought process. For full clarity, though, let’s take a trip back to 1991.

From a very young age, I was obsessed with hedgehogs. Such it was that when, in the early ’90s, I read of Sega’s upcoming mascot game, I felt compelled to tell the world. No one would believe me. I was obsessed with the Sega Genesis, which was fine but at that time no one owned or played the system. I was obsessed with hedgehogs, but in mid-Maine in the pre-Sonic era no one had ever heard of them except in association with me. So clearly I had gone off the deep end and was just making things up now.

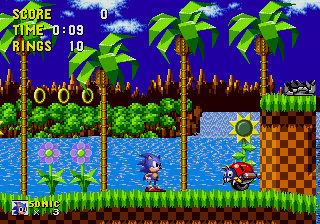

The game arrived, and it was very good, but — Sonic wasn’t really a hedgehog, was he. He didn’t look like a hedgehog, he didn’t move like a hedgehog, and he wasn’t really characterized the way you’d imagine. About the only parallels you can draw are that Sonic has spines and that he can roll into a ball. My mind got working.

Over the next couple of years, more Sonic games kept coming out to decreasing returns. Sure, each game had more stuff in it, but those were just things. The actual themes and spirit that made the first game so intriguing was being sidelined in favor of… stuff. It got so that Sonic the Hedgehog 3 was the last console game I bought or played until the Sega Dreamcast, another five years on. I was totally disenchanted with the direction that games were moving in.

And yet here I was in response, comporting more stuff into my own fetishistic ideas of propriety. I would draft my very own hedgehog game, the way that Sonic should have been. My hedgehog would of course be British, and as a Briton he would be enamored of all things tea. He would be reserved and conservatively dressed. As a hedgehog he would live in green places and only rarely stray out of his comfort zone. It would take a spectacular quest to shake him from his Hobbit-like indolence — something like a personal request from the Queen.

So we have a reluctant hedgehog with a tea obsession invited to see the Queen. What would motivate him to actually attend? Well, let’s make it tea with the Queen. What makes his journey an adventure? Maybe he needs to prepare for the visit. Let’s say he needs to bring supplies. What sorts of supplies? Goods for a tea party. So what goes with tea? If we’re being stereotypical, then crumpets.

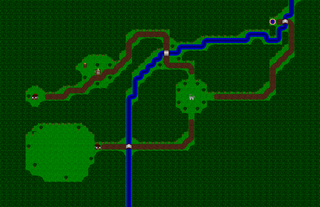

You can see the game taking shape here. Now we have a journey, and a scavenger hunt. Although there is a linear goal, this is a game about exploration and discovery rather than about speed (which is just as well for a hedgehog). Since it’s broadly linear but narrowly not, let’s scatter the levels around an overworld rather like Commander Keen‘s.

I’m not sure that this is very deep stuff, but at least the design concepts do come from the basic premise. If you squint, the game might even look a bit like satire regarding British conventions and the arbitrary decisions in mainstream game design. I don’t think any of that was deliberate. So far as I was aware, I made the game in earnest.

The game’s title is both a none-too-subtle nod to Sega’s game and a play on British public houses — or at least my adolescent concept of them.

In the end, Sign of the Hedgehog is more linear than I intended. You can thank those constant Game-Maker goblins of flags and counters. There was no easy way to prevent players from entering the same level over and over again to rack up provisions, which could only be a problem because Game-Maker will never reset special counters. Thus the player could keep collecting crumpets and 1-ups, dying, and then starting over to build up a wealth of currency and blow through the later levels.

Of course since the counters don’t reset this is a problem anyway, but at least making the level progression linear prevents players from abusing the system too terribly. In retrospect there are a few other unexplored solutions, but this is what we have.

The game was successful enough in my mind to warrant a sequel. I had promised one to registered users, and I figured that this time I would finally get a few orders. The orders never came, I got distracted by other projects, and the game never took shape.

To be precise, Sign of the Hedgehog 2 took a very general shape but I never bothered to whittle it down. As a result I have a slightly amended concept — this time Hedrick is collecting scones instead of crumpets; he now can toss crumpets like a Frisbee — and a new map screen, decorated with a poorly designed first level. To change things up, the map is now side-scrolling rather than an overhead view. You can tootle around the map all that you like, but there is nowhere to go.

One advantage to the side-scrolling map is that it does give a sense of scale and adventure. Compared to the bird’s eye view, you can judge how far Hedrick has traveled and what he went through to get there. I guess you could say it’s more subjective.

So far as I can tell, the one working level was more of a test than a real finished design. It consists of clear blocks against a night sky, presumably because I so enjoyed the clear blocks in the Commander Keen games. It was an easy visual effect, and it looked cool. Beyond that it had no purpose.

Already you can see my sensibility devolving, in several respects. But it would disintegrate much further.

The Adventures of Fred Earwigian is the nadir of my character-based design process. By this point I had been hammering that character button for a couple of years, expecting my game concepts to magically present themselves at the last moment and allowing the full projects to take form. In this case, that didn’t happen. Why not? Well, let’s see.

Fred Earwigian was not so much a character as a wacky name. I have no memory of its origin; just that the name arose somewhere before high school, and thenceforth again whenever life called for a nom de guerre. Around my third year of high school, the name crossed paths with a domestic catch phrase and inanity was born.

On one return from Russia, my mother imparted a story of crossed communications. One of her hosts had advised her on departure not to forget, as she heard it, her hair. In reality he was speaking of a stuffed rabbit, a gift from one of her Russian friends. The misunderstanding delighted her enough to turn “Don’t forget your hair!” into a common goodbye in my household.

By 1994, my well of ready ideas was dry. I began The Adventures of Fred Earwigian with nothing but the name, and eventually a title screen, expecting intuition to steamroll the rest into existence.

Based on the title graphic, I figured that Fred was rather slow — both physically and mentally. In physique and mannerisms, I envisioned him as a vaudevillian yokel with bits of Charlie Chaplin and Groucho Marx. In personality, my mind went to Steinbeck’s Lennie, from Of Mice and Men. I wasn’t trying to be obscure; these were honestly my cultural references as a teenager. I didn’t get out much.

When one thinks of Lennie, one thinks of rabbits on the farm. When I thought of rabbits, I thought of Fred singing “Don’t fergetcha, don’t fergetcha hare / Ba-dum, ba-dum”.

That became the basis of my game: a bumbling, slow-moving, dim-witted fellow looking for a lost hare. I couldn’t make it work. I couldn’t find the game. I couldn’t find a point to it.

I drew and animated Fred’s sprite, and I recorded him some voice samples. I drew up half a dozen scenarios, none of which fit. The game was stalled.

I threw the character sprite and title screen together with a map and background tiles from one of RSD’s demo games, and uploaded the mess to the semi-official Game-Maker BBS in Rockport. With the files I included a document pitching Fred Earwigian as a design contest. Whoever made the best game out of the available materials would win something or other. No one bothered. Quite understandable.

You’d think that my experience with Fred Earwigian would have taught me something, but any wisdom was a good decade off yet. In the meanwhile I had mistakes to burn.

The story continues in Part Four…