To catch up on the story to date, you can view the archive here.

So at sixteen I was a professional game artist. My work was still rough, but it was going somewhere. I had gained a little structure, a little ambition, and a huge mound of confidence. With guidance, these qualities can almost make high school bearable.

My period with Game-Maker began with what would have been my freshman year. At that time I was, if you recall, still dealing with old social ties. By junior year my life had stabilized a bit: I had adjusted to the school, and gathered a new wave of cohorts; I began to socialize more, and to spend time away from home. As I roamed, so too did my creativity. I began to write music, to learn to code, and to compose my papers in iambic pentameter. I may not have been brilliant, but I was uninhibited and I was curious.

I was also keen to show off. Whether or not I knew what I was doing, I had published six games. In the right social circle, that can go far — and this new crowd had no preconceptions.

Despite my recent crash course in discipline, I was still designing without a theory. Though my results had grown much more thoughtful and polished, and I had begun to stretch the technical and conceptual limits of my tools, to me a game was still about a character: one places a character in a scenario, then fleshes out the scenario using one’s knowledge of existing games and design tropes.

Add in a swollen head and new crowd of people to impress, and we have the renaissance of the insertion game.

There was a definite beginning. One of my associates was to spend his senior year in India. We had grown close since fall orientation, and had developed a pile of in-jokes together. I chose to give him a send-off, filled with all those jokes and hints of his own interests and personality — a fondness for martial arts, a blanket irreverence to cultural norms and sensitivities.

It helped that despite my knowledge of Tintin and Uncle Scrooge and an ostensible eleventh-grade education I had trouble separating my oriental stereotypes. Ninjas were from Asia, and so were snake charmers — and there was something in there about cattle worship. It was all part of the same pop culture muddle. Mind you, at this point I was in a prestigious private school. So I’m not sure what happened there.

With the prevalence of Ninja-based action games, I also had my choice of tropes and templates. Probably my favorite of Sega’s first-generation Genesis games was Revenge of Shinobi. Thanks to composer Yuzo Koshiro and the prominence of his name in the menus, this was also the game that made me understand that games were designed by specific people, each with his or her own voice, and that it was possible to follow an individual from one project to the next.

Revenge of Shinobi is one of those weird sequels, like The Adventure of Link. The original is a direct and merciless arcade action game, Sega’s response to Namco’s Rolling Thunder and one of many volleys between the two companies. As in Namco’s game you can flip up or down layers of a side-scrolling level. Instead of a spy, you play as a ninja. Instead of a gun, you have shuriken. In place of doors filled with ammo, there are scattered hostages. Touch one enemy and you die, but — uniquely to Sega’s game yet far from unique amongst Sega games — there is also a “ninja magic” button. It’s a panic button; press it, and everything around you dies.

The sequel takes advantage of its console origin by sprawling a bit. The character can now take several hits, and levels are less linear. There are now four types of ninja magic, that serve different practical purposes. The game is also filled with secrets and with weird unlicensed cultural references — some of which got Sega in some hot water when the original rights holders got wind.

More than structurally bold, the game is also gorgeous, distinctive, and varied — both visually and aurally. Although Koshiro only composed for this one chapter (plus a couple of Game Gear spin-offs), his music was so successful that his name is forever associated with the series. People just forget that he didn’t write all of the music. What’s all the stranger is that people sort of forget about Revenge. It’s the Shinobi game that was new when nobody had a Sega Genesis. It’s also the most elegant of the lot, and it was my starting point for Ninja Tuck.

I made the character was tall and thin, like Joe Musashi. I filled the early backgrounds with bamboo and secret tunnels. I even littered the starting screen with autumn leaves, that blew away after a moment. All was well, except that the tall character meshed awkwardly with Game-Maker’s limited monster sizes. Without getting really clever, the tallest enemies could only be half as tall as the character sprite. This was acceptable in some cases, as with the scattered cows and burning swords, but it got a little weird when I chose to include knee-high enemy ninjas.

I had the notion of building the game around short-range melee attacks, as in Ninja Gaiden. A problem that I had noticed in hindsight about Peach the Lobster was that the natural attack zone for a 40-pixel tall character tended to fly over the heads of 20-pixel ground-based monsters. Thus I drew from Joe Musashi’s powered-up melee weapon, crossed with Strider Hiryu’s Falchion — which is to say, a blade that is all swoosh and a swoosh that envelops all before the character.

Given that in RSD’s engine all attacks are achieved through monster birthing, there is not much leeway for preciousness. Melee attacks are hard enough when they’re a single, static monster block. A whole two-block sword swoosh takes some intense experimentation. Though in retrospect I can think of one or two better solutions, I eventually solved the problem with a single monster block that quickly shifts down as it animates. Good enough!

After the first couple of levels, my inspiration again shifted from Sega to Tecmo. Several of the later themes are inspired by either the first or the second NES Ninja Gaiden.

Finishing touches include a slightly pointless map screen informed by Commander Keen‘s overworld (itself informed by Super Mario Bros. 3) and a wealth of digitized sound effects. Most of these I recorded myself, and manipulated in Cool Edit. Some, such as the sound the apples make, were directly inspired by Adept Software’s little-known yet neato Zelda knock-off, God of Thunder. A few effects came later, when the object of this game’s tribute was available for recording.

As a final touch, I added morphing menus. As usual I teased the player with promises of a sequel, and even mocked up a few pictures to suggest what was in store for registered users. Maybe it was left-over ambition from my summer commission, but this time I followed through.

Often when I dropped in on my associate he would sing the refrain to a pop song that struck him as silly on some level. One of his favorite quotes was from Suzanne Vega’s “Luka“: “My name is Luka / I live on the second floor.” The way he sang it, I imagined Hervé Villechaize popping his head over the bannister to welcome a new tenant. Whether due to the accent or my own whimsy, I also misheard the name. Thus, continuing the series of in-jokes from our first game together, I named its sequel Ninja Tuck II: Booka.

Whereas my earlier insertion games were flimsy, half-hearted affairs, my work on Ninja Tuck had inspired me to new levels of ambition. Having established a basic framework, for my second go around I was determined to make everything as original and as flashy as I could. Thus aside from the sprite, I redesigned everything from the ground up. As in Peach the Lobster I designed all of the enemies around a common theme — in this case plants — and for consistency I drew all of the sprites and backgrounds in Deluxe Paint. I even dragged in Metamorf to animate some in-game elements.

Why I settled on the plant thing, I am unsure. To achieve it, I pulled on vague memories of all of my favorite botanical levels from the previous five years. Those included Sega’s Land of Illusion (the Game Gear sequel to the 8-bit port of Castle of Illusion), the Aquatic Ruin Zone from Sonic 2, and great swaths of Epic’s Jill of the Jungle. And then there were the monsters. It’s hard not to reference Piranha Plants, and the ones I had in mind were from Super Mario Bros. 3.

One of the later levels is based on a technique hit upon by James Faux of Eclypse Games, and used in his game Mortal Harvey. As an elevator rises, threats gradually present themselves; at the end of the ride, the floor opens up and the player moves on to the next level. In design terms, the level is all trickery. The player remains stationary, while the background animates; different columns of tiles shift at different speeds to create an illusion of parallax scrolling. Monsters slowly scroll down from above, to create the impression that the player is rising to meet them. My implementation was rather clumsy, but these sorts of levels do add variety.

James Faux also helped me to address that final bugbear of RSD’s engine, original music. For months I had been fussing with Amiga-styled music trackers, which consist of low-res digital samples keyed to MIDI data. Compared to the FM synth that Game-Maker supported, tracker music seemed like the way of the future. Furthermore, this stuff was easy to write. Thanks to the mid-’90s demoscene explosion, there was a free tracker for every UI flavor or song format one might like.

There were no obvious tools for RSD’s preferred format. I knew that someone had to be writing these .CMF files, as Epic Megagames used them for all of its early projects — Jill of the Jungle, Solar Winds, Brix. I was tempted to rip this music, which was as simple as looking for the correct headers and renaming the file extensions, but again I wanted to do something original. If I couldn’t, then to my mind it was better to keep using public domain material, even if it meant recycling the same pieces in every game I made.

For months I had been nagging RSD about better music support. I now know that there were complex plans on the board, but at the time my whining was met with silence. By the time of Booka, my petulance had reached a peak. With the aid of some awkward command line tools, James Faux and I were able to convert simple .MOD files to MIDI, and then to .CMF. It was a process of trial and error. Usually the result sounded like an angry modem. With a few tweaks, it might sound like an out-of-tune kazoo. Awful, but original!

Thus I scored my first game. Two or three tracks are by James Faux; the rest is all me, mostly to the game’s detriment. And yet, I was proud. Later I lopped off part of the intro music, adjusted its voicing, and turned it into the A-J Games theme.

After this experience I contacted RSD, and told them that I was “on strike” until they got the music situation in order. I wasn’t going to squander any more energy until I got the features that I wanted. Thus I rode out high school on small-scale games and half-baked experiments, waiting for a cue that never came. It would be years before I tackled and finished another game of this ambition.

Take Ricci’s Cow Hunt. I barely knew the fellow in the central role. He was a class clown; he liked cows; I worked from there. It began as a single level: character, item pickups, background. Whereas the sprites are Deluxe Paint beasts, the level is built from a small collection of simple bitmapped tiles. I drew them dot-by-dot in RSD’s Block Designer tool, then reskinned the first level of A-J’s Quest. The results were clean and bold, and stood out better than many of my gradient-fill blocks. Compared to, say, Crullo, this simple level looked and felt vibrant.

It’s not that I set out to be different; I set out to be lazy. I designed a character based on a slight acquaintance because I was bored, and I wasn’t about to invest the time and energy to build a real game around him — so I puttered in the easiest and quickest tools to hand. It just turned out that a lack of ambition equaled a decrease in affectation. I wound up concentrating more on the task at hand than the process that I had built up, and my basic sensibility took control.

So I had one level down, and it was kind of nice. Next step? Design another level — a completely different one, with a new tile set. Then another, and another. For over a year I continued to putter with Cow Hunt, adding new levels as the muse struck. When I had ideas for a new technique, I would pull up Block Designer, whip up a few tiles, then turn them into a level. Gradually the game became rather like an Ikea show floor; every level served to suggest a new way to mold and paint particleboard. There was nothing to the game besides touring from the entrance to the exit, but it was a pleasant journey.

I installed the game on the computers in the school lab. Whenever there was an update, I would make an announcement in the autoexec.bat files. I don’t think anyone really took care of those machines, as I got away with murder. As time passed I noticed unfamiliar names in the high score lists; it seemed that people were playing. With an apparent audience, my ambition grew. My levels grew more complex, with reversed control schemes and hidden passages. Thanks to this feedback I also realized the game’s object. There were few threats or serious obstacles, but it took a dedicated player to collect all of the cows. Every cow lent the player 100 points. Thus, the game was all about score.

How novel. Since Pac I had been trying to break or sidestep the engine’s location-based objective structure, and to backpedal to something more basic. Something pre-Miyamoto. Here it happened by accident, in a game that I hardly cared about, after I had given up on serious design.

Something else kind of happened. Since the game’s mechanics are so simple as to be almost nonexistent, the level design wound up pretty focused on the character’s abilities. Since the goal in any level was just to show off some new concepts before sending the player off to the next tile set, the design wound up focused more on exposition and forward momentum than on interrupting and frustrating the player. Cow Hunt is one of the first games I made where the player is free to poke around without judgment or severe consequence.

More than once I have heard the later, more confined levels compared to Mega Man. Although that series tends to typify judgment and severe consequence, I think I see what they meant. Peril or no peril, the clean bitmapped backgrounds and the forward momentum make Cow Hunt feel more like a real game than some of my greater efforts. There is a familiar sort of rhythm and flow, and the player feels prepared to handle every next beat as it comes.

I think on some level I noticed this rhythm, as late in the process I added the first level of Super Mario Bros. as a secret area (an area that would later form the basis of Jario!). There’s little to do here aside from run and hop to the exit, but I guess that was the idea. I think that I knew I was approaching something primal, or fundamental, about game design. What that was, I couldn’t have told you. I doubt I would even have described it that way. I just knew that things were working strangely well.

With a few new neurons buzzing, I decided to get deliberate again. I plucked a somewhat closer associate, in the shape of a former roommate with a shambolic persona and an affinity for R.E.M., and sketched out a grand plan.

Before I seriously ramped up production on The McKenna Chronicles, I settled on a rough story progression then blocked the progression out into levels. The initial scenario and structure were inspired by the zany historical fantasy of WolfTeam games like El Viento and Earnest Evans, crossed with a passing awareness of The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles.

The WolfTeam games are full of fast and quirky action, huge setpieces, and long scenes of interstitial exposition. Accordingly I gave the character a run function, precise Castlevania-style jumps, and a gimmicky, experimental means of attack; and I took advantage of Game-Maker’s new multimedia features to connect the dots between levels with elaborate cutscenes.

I think that, in the vein of Earnest Evans and Castlevania, I wanted to give the character a whip — which in principle would be a good follow-up challenge to the sword mechanic in Ninja Tuck. When I hit a wall, my brain slid laterally to Dark Castle, the crackly Castlevania-styled game for the classic Mac. In that game, the character slings rocks at airborne and ground-based rodents. Although I couldn’t replicate the precise mouse-driven aiming, I could add some realism by making the character lob his stones in a wide arc. Combined with the precisely measured jumps, I felt a mechanic like this would add some strategy and open up neat possibilities for level design.

The simplicity of Cow Hunt must have connected a few key synapses, as my whole approach to design had changed almost like magic. Previously my characters’ movement had always been vaguely defined, and their abilities slightly considered. If a character was to jump, his animation took him somewhere diagonally into the air. If he was to shoot, then at best the projectile might be matched to the animation. Since my command of the design was so hazy, I put only the most nominal thought into how a character would interact with its environment. So long as a task was possible, I was satisfied. “The player will figure it out,” I thought. Never mind that figuring it out often meant glitching the engine and relying on blind luck.

With Chronicles, that approach is no longer an option. The character jumps a precise distance up and over. If the character is to land on a platform, one needs to measure the distance between footholds. Too few tiles, and the character will sail over the target; too many, and he will fall short. Likewise the character’s default weapon has a specific arc to it with certain areas of effectiveness, and the character’s running momentum will only carry him so far if he should stop and slide.

So on a basic level the levels are mapped out according to the character’s abilities, in such a way as to regularly introduce new challenges and explore new uses of those abilities. On a broader level, the levels are also scattered with secret passages full of treasure — treasure that may be used to buy character upgrades, which generally allow the player to blaze through the game with less and less caution. The promise of these upgrades encourages exploration off of the most direct and obvious path through a level, and also gives reason to replay an area.

Even more broadly, Chronicles is one of the few games since A-J’s Quest that I extensively planned, as compared to charging ahead in a blind rush to the end. There was still a large element of improvisation; I don’t think the game’s full arc came into focus until I finished a draft of the first level. Even so, from very early on I had the entire game laid out as a series of labeled blanks. All I needed to do was procedurally fill them in, and the game would be finished. You can probably guess the punchline here.

Out of six planned levels, I worked on four and completed just two. It started off well enough. As with Cow Hunt, the active design began with a Deluxe Paint derived character and meticulously bitmapped backgrounds. In this case the monster and item sprites are also largely drawn in Block Designer. After the first level, the game took its own odd path through space ships, alien planets, and Monument Valley.

The second level, largely informed by Commander Keen, introduces themes of identity and deception. As in Sega’s Alien Storm, monsters begin to disguise themselves as items, background elements, and even as the player character. From here I built on the sprite morphing from Ninja Tuck II, supplementing the raw output of Metamorf with careful cleanup and bitmapped animation.

For later levels I imported textures from NASA photographs, and filled entire tile sets with large self-contained structures drawn in Deluxe Paint. I also drew and animated several full-screen cutscenes, frame-by-frame, and compiled them with some awkward command line tools into the preferred .FLI format.

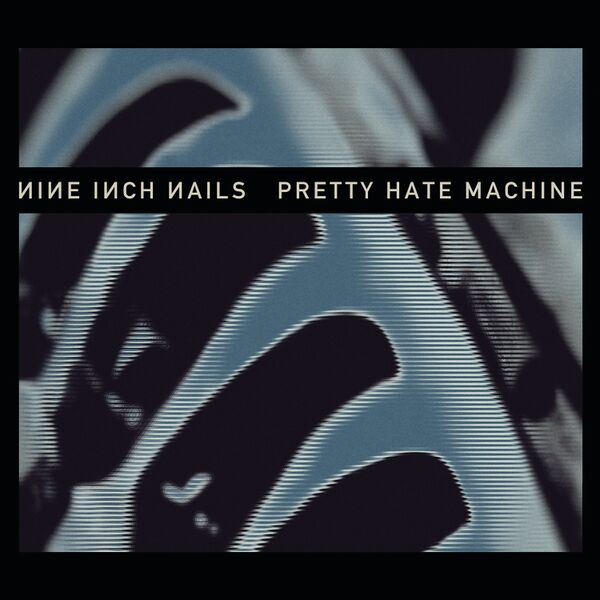

And then… it was over. I think I told myself it was due to annoyance with lingering issues like the music situation. I wanted R.E.M. styled music, to reflect the fellow in the starring role. Though I had written music for Ninja Tuck II, the method was a headache to implement and the results were a headache to hear. I think maybe I was feeling fussy about control mapping and collision issues.

The real problem may have been in the planning. I may have overwhelmed myself, when I laid the whole game before me as a task that I obliged myself to fulfill. Or maybe, as with RÅdïp, I pulled a Hitchcock. Having planned the whole game in principle, the act of realizing it bored me. I knew where things were going, and my head just had to keep moving forward. Chugga chugga chug!

Whatever. It is clear that my patience with the game engine was wearing thin.

Case in point: my sole self-insertion game, Watch Me Die!. By my senior year, Game-Maker was more or less history. I had moved on to music, poetry, short stories, and illustration. Everything that in the past might have tied into game design was now set free.

I even co-edited the student literary magazine, Cereal. It consisted of bad poetry laid out in PageMaker then Xeroxed onto two or three sheets of legal paper. By my second or third issue I was irritating my co-editors by editing and designing the magazine alone. In my defense, it was nearly impossible to get them in the same room at the same time. Though I may have missed out on the spirit of collaboration, I still got the thing published.

For the purposes of Cereal, each editor had an abstract doodle as a portrait. One consisted of puffy hair, glasses, and a mouth. Another, a backwards baseball cap and some facial features. Mine was oval glasses, a nose, ears, eyebrows, and a few dangling strands of hair. This caricature formed the basis of the character in Watch Me Die!.

From the title on down, the game is a work of ironic apathy. I was creatively tired. I had stopped trying to be flashy or to impress anyone, and had returned to doodling in the vein of Ricci’s Cow Hunt. In the course of an hour or two I would knock out a tile set and a character, then piece together a couple of simple levels. In the case of this game, I made a point of my fatigue. In videogames the most basic measure of success or failure is life or death; even that was beyond my interest.

The character walks as slowly as possible, and looks frenzied while doing it. The idea was to instill a sense of futility. There is also a “skip” move that allows the player to speed up travel at the expense of some control. It is easy to skip over a ledge in one’s frustration with the pace of movement. The character also jumps very precisely and abruptly, with little fanfare. You want the character to cross a gap, or climb an obstacle? Fine. There, it’s done. Happy now? The lack of enthusiasm is almost droll.

There are items, and to contrast with the understated character motion they all overstate their importance. Simple pickups might be accompanied with a Hallelujah choir. Hearts can’t be simple heart shapes; they need to be big, throbbing organs. Again it’s all passive frustration with the design conventions and expectations that I felt no joy in rehashing.

Within all of this, something began to click. I was bored enough with the post-Miyamoto tropes that I had sort of transcended any rote obedience and begun to search for something, anything to interest me in the design process. What I came to focus on was the moment-by-moment interplay of the character with the environment. Everything else kind of fell away.

From the player’s perspective, Watch Me Die! is all about the controls. They’re simple, crisp, and accurate. The levels are built around the character’s abilities, not to do the player any favors but rather to see how well the player responds in a given situation. Death is easy, but if you die it’s because you screw up. And that’s fine. The game doesn’t dwell on the fact, so neither should you. Just start again from the top, and try not to die again.

It’s only when I gave up that my games began to feel right — less like the work of a fan desperate to replicate something that he loved, and more like a deliberate, professional product. Condense the control mapping so that all the jumping is on one key and the skipping on another, and you could stick Die in an arcade cabinet and it would almost make sense.

Everything good happens only as an afterthought, and so it was with my Game-Maker career. Some thirty-five games in, finally I made something playable — just in time for me to change tracks and leave all of my experience behind.

Or very nearly. In our final chapter we will see the results of design unchained. If you’re going to go out, you might as well go with a bang.

Next: Learning to let go.