This is another unpublished article — ostensibly a glossary for the end of a “New Games Journalism” anthology edited by Kieron Gillen, friend to all woodland creatures. It was to have been published by O’Reilly Media; as tends to happen, there was a management change and the new guy was no longer interested in the book. At least I got paid… in a check composed in pounds sterling, that my bank refused to cash. Hm. Well, here it is.

As few of our readers are likely familiar with the intricate jargon involved in videogame writing, I have been asked to compile a list of common words and phrases found throughout this volume. Although some of these words may look and may even sound familiar, a wise traveler takes caution when straying into unknown land; even an innocent gesture may find you on the wrong end of a dagger or the wrong side of a jail cell. Before acting on any of the advice contained prior, and certainly before laying judgment on the claims put forth in this text, please study the following index and integrate its contents into your daily routine.

NOTE: It may help to copy these terms out on a sheet of paper, and to repeat them daily. For those culturally blessed with right-handedness, try writing the terms with your left hand for added practice and agreement between both of your mental hemispheres. For those accursed to live in a world not designed for their grasp, wield your pen alternately to those before you.

A subjective form of communication that uses metaphor to suggest a vast yet implicit web of common understanding between two parties, often on a subconscious or an unconscious level.

Anathema to the Gamer.

In a videogame context, the in-game character or object that represents the player. In the cases where the avatar is anthropomorphic, it usually takes the form of a hyper-masculine adult male or a woman wearing three square inches of clothing. More recently, Japanese games have replaced the former archetype with an androgynous (or even hyper-feminine) male lead. This is all more comprehensible when you understand the intimate bond between a player and her on-screen persona. The player’s avatar becomes, in a sense, her closest companion on her lengthy journey through the gameworld. Especially in a modern 3D adventure, it is important to find an avatar whose ass the typical player will enjoy watching for hours at a time.

Every medium is a study of specific properties of the human experience. Sculpture is a study of form; music, a study of tone. Videogames are a study of the relationship between cause and effect. That is to say: where videogames exist, experientially, is in the feedback loop between the player and the gameworld. The player acts upon the gameworld, and is given a response (or lack of one). This response then becomes the basis for further reaction. It is this ping-pong communication with one’s environment that defines the medium.

The goals set before the player mean relatively little unless the player has opposition to overcome in order to fulfill those goals; any screenwriter or novelist could tell you that. This opposition might take the form of a snarling man with a mustache, a lack of communication between brothers, or a lingering sense of guilt over a past deed. Conflict is the manner in which opposition is addressed. In a videogame, the solutions to the above problems would be to stab the man with the mustache, to stab your brother, then to fire a laser-guided missile at your guilt. Metaphorically, perhaps.

In most videogames, violence is the major or sole source of conflict. As every videogame must sustain player interest for fifty hours or more, each requires an parade of weak and generically evil characters to kill. These are known as your enemies. An enemy can be easily discerned from a non-combative NPC in that any evil entity will hurt, kill, or infect the player’s avatar on contact.

This design philosophy has its roots in early drafts of the Christian Bible, in which Jesus preached social paranoia and an ethical code based in Darwinism. (These sections were later revised in part, from fear of alienating Southern Baptist ministers.) These teachings were later adopted as a social code during the Reagan administration, during which videogames initially flourished.

In life, experience is accumulated through keen observation, trial and error, and persistence. A person’s accumulated experience is the context from which she can derive meaning from the events that make up her life, and from which artistic communication is made possible. Although these events will call on a limited number of templates, it is the way the elements are balanced that gives us each our unique perspective.

In videogames, experience is accumulated by exiting your town borders and stabbing bunny rabbits. You can tell how much experience you have gained by the numerical tally in your sub-menu. With enough experience, you will advance to the next level (of advancement) and possibly learn fire magic.

Doesn’t exist. See Liberty.

An objective term for the liberty allowed within a given gameworld; the things that a game lets you do, and therefore the elements that make up the player’s potential. Often misapplied to mean how a game feels to play – whether the jumping seems solid, whether attacking is satisfying. Those are mechanical issues. This is just about potential: what you can, hypothetically, do.

On an even keel with graphics, and far more important than sound or replay value.

Creatures whose personal identity is rooted in a lifestyle built around videogames. Typically conservative, defensive, and isolationist in attitude – especially when it comes to videogames, especially the particular videogames in which they are most deeply invested.

Notable subspecies: Hardcore Gamers, Retro Gamers, Obscure Gamers, PC Gamers, Console Gamers, Fighter Fans, RPG Fans, Shooter Fans, Technophiles, Wilson’s Golden Band-Rumped Gamer.

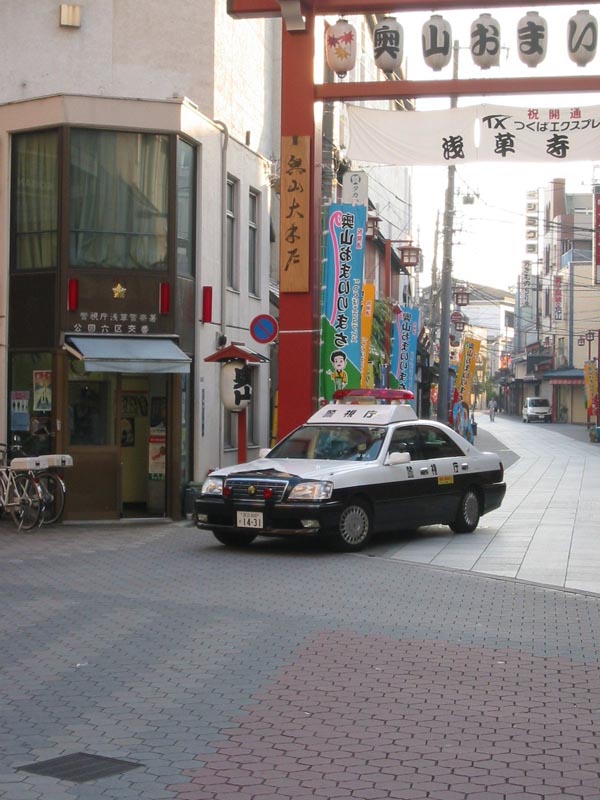

The artificial space given to the player to navigate, including all of its rules, logistics, background, and inhabitants – the way all of these elements cohere to form a tangible place – that’s the gameworld. Pac-Man’s gameworld is limited to an endlessly-repeating blue maze filled with ghosts who re-spawn in their central nest, corridors lined with cookies, and the occasional bouncing piece of fruit. Shenmue’s gameworld is a limited recreation of a mid-’80s Japanese suburb where you never have to eat, where the kids all want to wrestle, and where people actually know whether or not they saw a black car on the day that the snow turned to rain.

A gameworld is largely defined by the liberty allowed the player; its verisimilitude, however unrepresentative it might seem of the “real world”, relies mostly on not suggesting any more possibilities than it actually allows. Once the player starts to question why a reasonable option is unavailable to him – say, stepping over a line of police tape or walking down a corridor blocked off by an invisible wall – the illusion is shattered. In its abstraction, Pac-Man has a highly believable gameworld; few would question, for instance, why the player can’t merely jump over the maze walls.

A term used by gamers and game journalists to refer to the visual presentation of a gameworld. The implication is that boiling down a game’s appearance to an objective-sounding term will allow an easy (perhaps even numerical!) assessment of worth. Old games, like the original Legend of Zelda, have bad graphics. New games, like the newest car racing or Madden game, have good graphics. Unless they don’t map enough mips or buffer enough Zs, that is.

Alongside gameplay, one of the two most important review criteria.

The means through which a player may interact with the gameworld. Interfaces have both a physical and a design component: physically, you have the means through which commands are entered (a control pad, joystick, power glove); by design, the player is given feedback through a display device. For example, the game tells you to hit “A” to open a menu. You press the “A” button on your controller. This brings up the menu, which gives you further information to inform future actions. An interface is the objective aspect of the cause-and-effect relationship between player and game. The subjective aspect is known as mindspace.

Liberty is freedom within bounds. Or, perhaps, the illusion of freedom. According to most codes of ethics, a person has liberty to do much as he choose so long as he not negatively interfere with the liberty of another. As conscious creatures, we have the liberty to do whatever our psychology, our circumstances, our physical laws allow – which in the end is not very much. You can pick the 2% or the skim milk, but in a sense the decision is already determined by your nature, by every event of your life to that point however inconsequential it might seem, and by factors completely outside of your control (mostly relating to the liberty of others). Even your standing at the cooler door, making up your mind, is the inevitable outcome of prior events.

Though you may have no true freedom, you have full liberty to do what you will within the means and situation provided you. Though your decisions may objectively be preordained, you subjectively have the option to choose whatever path you wish. The same is true of every gameworld. Although Liberty City may allow you a broader scope of options than Pac-Land, both offer the same liberty within the narrow box handed you. If a game has strong verisimilitude, the bounds of your liberty will never occur to you and you will simply accept the world as it is given.

In real life we have laws – physical laws, social laws, ethical laws. Instead, videogames have mechanics. In theory, mechanics exist to define the boundaries and establish the potential of a gameworld. In reality, ninety percent of all game mechanics exist to make one genre piece distinguishable from another.

On its own, a videogame is just a collection of code burned into an optical disc or some other storage medium. Videogames are, in a sense, pure ideas. There is no physical element to them. Further, a tremendous background of technology and service is required to experience a videogame. All of this investment exists to create an absorbing mindspace for the end player. The mindspace between player and game is where a videogame actually takes place; where a player serves as protagonist to his own gameworld experience, according to the liberties alloted him by the game mechanics. The greater the verisimilitude of the gameworld, the more easily a player’s mindspace is retained. Mindspace is the purely subjective component of the cause-and-effect relationship between player and game; the objective component is known as the game interface.

The manner in which a story is told. In film, narrative is a facet of editing and framing. In a videogame, narrative comes from playing. Asteroids does have a story, as far as it has a narrative. It happens to be a story of a lone space ship and its ultimately doomed goal to clear the space around it of dangerous space rocks. The particulars come in the telling – that is, in the playing. How long the ship lasts, how well it does, what close calls it has, are all up to the player.

The greater the scope of liberty allowed a player, the more undefined the narrative.

A non-player character is an actor on the stage who is strictly controlled by the script, rather than by a human mind. In effect, an automaton placed within the gameworld to give it the appearance of population outside the player. Sort of creepy. Generally considered distinct from an enemy, in that NPCs are given the illusion of personalities and lives of their own, whereas enemies only exist to be evil. NPCs are typically a barrier to verisimilitude, in that both by nature (as living props) and by technological limitation, they will never behave in a completely believable manner.

Life is but a stage, and we are all players.

latent possibility. The greatest achievement of verisimilitude is the suggestion of endless potential within a given world – the sense that anything could be out there, that you can do anything you want, that a miracle is just around the corner.

The illusion of reality, which in most cases is achieved through not giving the audience cause to question the reality at hand. Postmodernism gets some of its kicks though turning verisimilitude on its head and bringing conscious attention to the seams of a given work. On its own terms, though, this is just another level of reality, with its own layer of verisimilitude. For a work to succeed, we need to believe in it somehow, even if that belief is a belief that we shouldn’t believe in it at all.

Different from suspension of disbelief, as with enough verisimilitude disbelief won’t even enter the picture.

The only important form of videogame conflict, violence involves the malicious harm of, or the intent to harm, another being. Violence can be overt and physical; some figures like Mohandas Gandhi more broadly interpret it as any negative effect, however inadvertent, one person might suffer at another’s hands. Jean-Paul Sartre sees human communication itself as a form of violence; merely by interacting with another, we cause damage on some level, for both parties. Given that the entire nature of videogames is a study of communication, perhaps this says something.

Videogame violence is of a literal variety: one character brandishes a blade, and attacks the next. Oddly, although violence both forms and resolves nearly every videogame conflict, it is rare that videogames explore the repercussions of violence. Ethically, it is perfectly fine for the player to shoot ten thousand soldiers in order to save a single comrade, because the enemy soldiers are not real. They have no lives, no personalities, no bearing on the gameworld. They are simply evil incarnate, much like the “Communists” and “Terrorists” of American history. Perhaps intrinsically, the only force that matters in a gameworld is that of the player, and if the player is to continue feeding quarters, or is to feel generically satisfied with his fifty-dollar purchase, a videogame must encourage the player to feel not only justified but victorious in his actions. This is the state of videogames today.

Special thanks to Tim Rogers, Brandon Sheffield, Shepard Saltzman, Andrew Toups, Amandeep Jutla, Thom Moyles, James Freeman Rinehart, and Christian Culbertson.