The History of A-J Games: Part Seven

To catch up on the story to date, you can view the archive here.

Did I say that things got better? Maybe eventually, but first we need to backtrack a bit. So far we’ve been looking at character games. Some of the characters are fictional; others are based on people I knew or who I didn’t know were fictional. Whatever the origin, these games are based more on objects than subjects. They didn’t start out as theories or experiments, or attempts to express a thought or feeling though the psychology of game design. Maybe in dropping these objects into the pond I drew some subjective ripples, but in principle my methods would have fit right in at THQ.

What we’re going to talk about now is another level of objective. You will have noticed my constant references to other people’s games — mostly professional, mostly derived from the Miyamoto-fed Japanese school.

It’s normal enough for one artist to look to another for inspiration; art is a form of communication, and nothing speaks to an artist like art. It’s also normal for a novice to model his or her work on something familiar. You can’t begin to speak your mind until you know the language, and you have some idea how to fit the pieces together to express ideas. An illustrator traces to get a sense of form; a musician may spend a lifetime interpreting other people’s music before he feels comfortable writing his own.

I guess what I’m doing is justifying creative laziness. I applaud the growth of new forms, and there will be a period of grasping before a form takes shape, but I always wonder why people will take an existing recording, loop it, and add a few riffs on top. If you drew inspiration from Abba or some Motown artist, great. Build on that. Then, erase your tracks.

There can only be so many Andy Warhols, making a statement about our perceptions and expectations of art. There is a place for collage and documentary, and cultural commentary. Generally, if someone is claiming a recognizable hunk of someone else’s work as his own, to me that speaks of a character flaw. It says that the derivative artist doesn’t give a shit about the original artist, about his or her own reputation, about the integrity of either the original or the derivative art, or about the intelligence of the intended audience.

Unless it is very well signaled I don’t really buy the tribute angle, and I have little patience for pastiche. I hate it when people quote from presumed authorities to make their own points in an argument. I cannot abide organized systems of belief or thought. If you can’t find your own thing to say, in your own words, I don’t want to hear from you.

So this chapter is about my own hypocrisy. I don’t know what parts to damn and what to excuse, so I’m laying out the whole problem now. I also have problems with absolute perspectives; as strict as I may sound, I know that nothing is ever that simple. There’s the principle, then there’s pragmatism. And sometimes to embrace the principle one has to spend a while fighting it.

Take piracy, in the modern lawyered-up creative sense. Is it wrong to copy someone’s work? Maybe; why are you copying it? And what’s the result? Did it do more harm, or more good? I think that copyright should expire after fifteen years, as you can’t control an idea once it gets into the DNA of public thought — but I also think that the original author should be able to enforce attribution. Organized chaos, if you will. Evolution with footnotes.

That doesn’t stop my own guilt when I indulge (as with the borrowed images in these posts), or temper my annoyance when someone builds on my work. I guess I should just get over it.

My least shameful tributes are those where I feel I built something original out of the borrowed material, however wholly I may have borrowed it. That isn’t to say that my divergence was deliberate. How much if art is really deliberate anyway? Anything that matters is usually an accident of technique or circumstance, and anything you try to do tends to end up obvious and meaningless. Why is that? Well, think about it. If you can’t even surprise yourself, how interesting do you think your ideas really are?

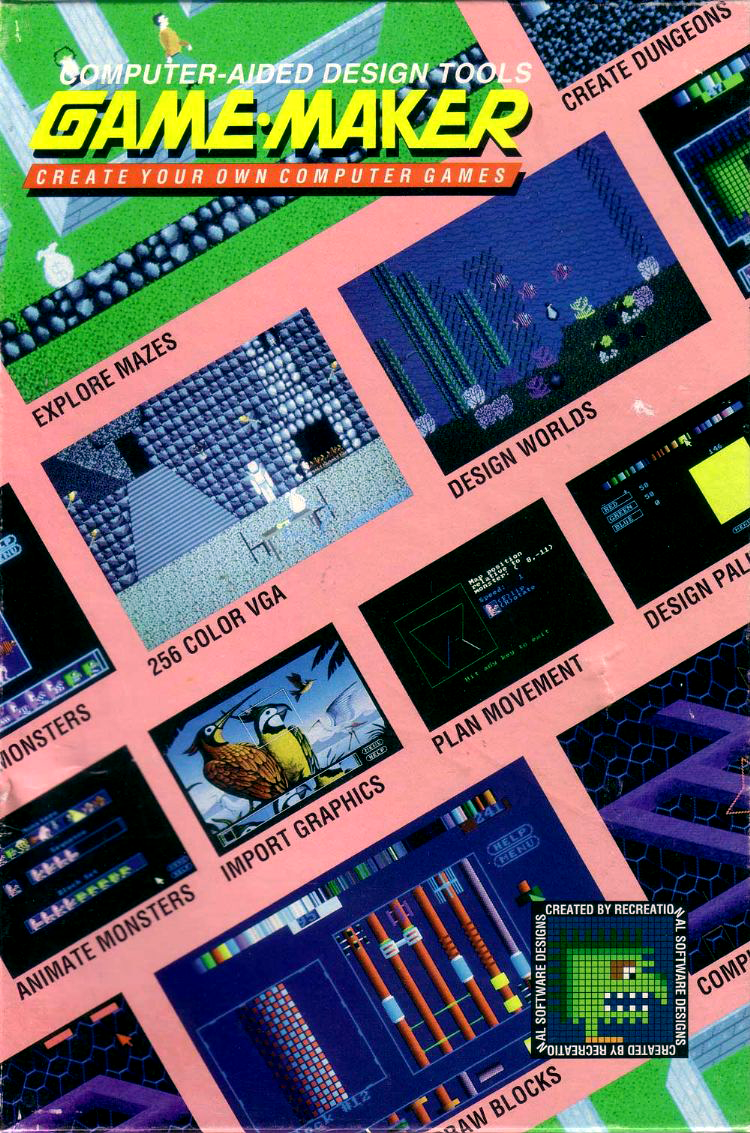

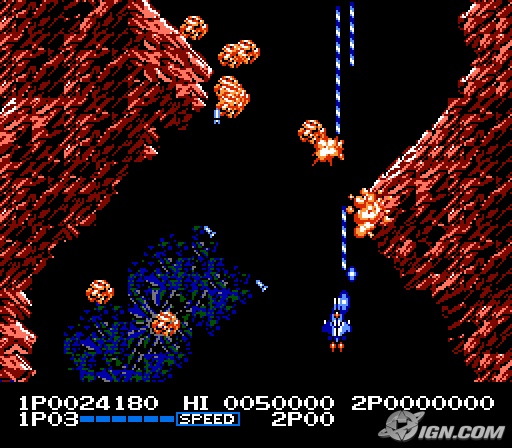

Nejillian Flux was supposed to be a carbon copy of Gradius, maybe with a bit of Life Force for variety. As it happens, RSD’s Game-Maker is a poor platform for scrolling shooters. They knew it, and improvements were on the radar, but they never quite happened. So I found some workarounds. Not good workarounds, but distinctive ones.

This was an early project. I can tell you how early because of an even earlier pastiche. When I was finishing up Linear Volume, I asked my client for a title. Linear Volume, he said; I went with it. I also mentioned my next project, a scrolling shooter based on Gradius. He told me to call it Nejillian Flux. It sounded good, so again I went with it.

To this point I had designed, I think, six games — three platformers, and three adventure-RPGs. Although I completed most of them, only one of those games — A-J’s Quest — had been very successful. I figured maybe it was time to try something new.

I hit three technical problems: scrolling, map size, and power-ups. The most fundamental of those is the scrolling, or rather the lack thereof. Game-Maker only supports a strange shifting-focus scrolling, where the camera always tries to place the character sprite 1/3 of the way from the opposite edge of the direction of the character’s motion. If the character is running right, the game wants to put 1/3 of the screen to the left of the sprite and 2/3 to the right. The same principle goes for all four cardinal directions, which in a game with free movement can cause the camera to lose all reason.

There are ways to work with this trait, but for a scrolling shooter it is fatal. The two common workarounds are to point the background gravity sideways, or to adjust the character motion so that it must always move in one direction. Neither really works, but if done well the player gets the general idea.

A related problem is in the engine’s strict map dimensions: exactly 100 pixels, square. That’s 6-1/4 by 10 screens, which may be fine for an overworld map. If you’re scrolling exclusively to the right, that means in less than 7 screens you will loop back to the start. Think of Eugene Jarvis’ Defender.

My solution was to double-decker the levels, and to hide a tunnel between the two stories. The player would keep looping until he or she found the passage, from which point the level became linear until the end. An eccentric choice, but it was the best I could think of at that time.

I also ran into problems with the weapon upgrades. The engine does not allow for arbitrary character or control states, so you can’t simply pick up a weapon and use it. The only solution is to give any weapon pickups a hierarchy, and to limit their ammunition. So if you pick up a very powerful weapon, you may only have 20 shots. When you have expended those, you default to the next most powerful weapon for which you have ammo. If you want to use one of the lesser weapons, then first you have to blow through the greater ones.

Then there is the question as to what makes a tougher power-up, as Game-Maker is very black and white about power levels. If your weapon has a level of 150 and the monster is at level 100, then the weapon kills the monster. If the monster has a power of 151, then the weapon does nothing. So weak weapons are pointless, and powerful weapons are perfect. If you’re creative you can find some lateral solutions; in 1993, I was not that creative.

Game-Maker’s engine was always a point of contention and curiosity. With a little lateral thought, it was capable of many things. Its odd and often simplistic arrangement resulted in dozens of unlisted features, and encouraged creative problem solving. Its comfort zone, though, lay in top-down action adventure games. It had the inventory and the four-way scrolling of a Zelda or Crystalis, and it was much happier when one avoided things like gravity or nuanced control schemes.

There are three ways of approaching a set of limitations. You can fight them, you can work within and around them, or you can subvert them. If you fight them, generally you will lose and your work will suffer. If you subvert them, you can produce very clever tricks to wow your peers who know what you’re up against — but chances are the tricks will be glitchy, and will fail to impress anyone else. If you work within the limits, maybe the walls won’t be so obvious and your work will be able to stand on its own merits.

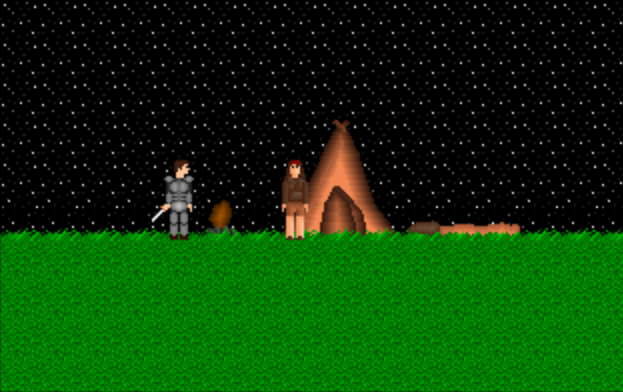

Link vs. Gannon was my first go at working with the engine. This was maybe two or three games before Nejillian Flux. It was clear to me that neither platformers nor RPGs worked to Game-Maker’s strengths, so I relented. If the engine was geared toward Zelda, as it appeared to be, I figured I might as well see how close it could get.

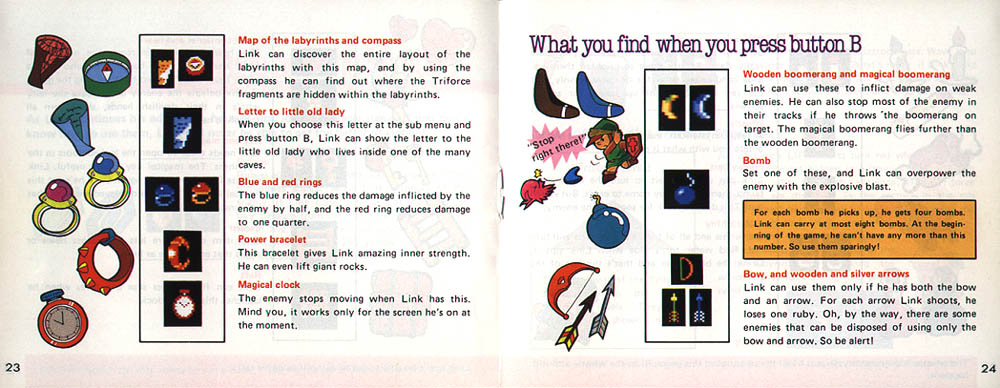

The NES Zelda games are amongst my favorite things ever; the first for the actual moment-to-moment design, and the second for its weird atmosphere and its bold deviation from the original. I loved the claustrophobic focus, but I also loved that sweeping adventure too large to record in every detail — so I combined the design and dungeons from the first game and the free-roaming world of the second. Points of interest were scattered around a huge area, broken up by fields, rivers, hills, and bridges.

I doubt I meant to finish the game, and indeed Link vs. Gannon is the first that I left incomplete. I just wanted to figure out what the engine would handle well. The frustration came early on, when I realized that I was fighting far more than I had planned.

I often think of Game-Maker, if it just had X feature then it would be complete enough and I could work with all of the other problems. When I was in high school, I really needed a better music format. At other times I needed text boxes, or more detailed control mapping, or more complex enemy logic. On reflection, I think the sorest omission is the ability to make pervasive changes to the gameworld.

Here’s what I mean by that. In Game-Maker’s engine, the character can interact with the background — change blocks, pick up objects, kill monsters, and increase abstract counters linked with things like keys and locks. If the player dies or leaves a level, all changes to that level are reset — yet all counters remain as they were. So if you have a level that contains a precious item, you can pick up the item, leave, return, and pick it up again. If you kill a boss then return, the boss is back. And so on.

For a game like Zelda, that is all about exploring, discovering precious tools, and making slow significant changes to the world, it is disconcerting when nothing the player does can stick.

There is a way around this issue, but it involves a bunch of busywork and a tangle of logical wires that are very easy to lose track of. I also didn’t hit on the solution for a very long time. If I did, then evidently I never felt it was worth the effort. And that was my ultimate decision with Link vs. Gannon; it wasn’t worth the energy to figure out how to make it work, or to draw custom background tiles, or to put real work into the level design. I filed the game away, and for a while I continued with my own projects.

Over the years, the counter-and-flag issue kept raising its head. If I tried to do something complex, it was the lack of flags. If I tried to do something simple, it was the counters that wouldn’t reset. One of my more successful games, curiously enough, was a very hard Pac-Man clone. I asked that anyone who enjoyed the game simply send me a postcard, saying “I like Pac!” I got maybe half a dozen cards over the years. Nejillian Flux also traveled a bit. For a while it seemed I couldn’t browse a shovelware CD or Russian shareware site without stumbling over the game.

The problems with Pac were twofold. First, there was no way to contrive it so that power pellets made the character immune to the enemies’ touch. I got around that by turning the pellets into projectiles that the character could spit out. More worrisome is that if the player died before eating all the dots, the counter would carry over but the background would not. In retrospect I’m sure I could have contrived a way to drain the counter at the start of a new life, but the solution I found was to give the player only a single life. One life, one hit point. To reach the end, you have to play a perfect game. Not the most elegant solution.

If it wasn’t the flags and counters, it was a lack of arbitrary character logic. Pac can’t eat ghosts, and Mario can’t stomp enemies. For kicks, one of my later projects involved transcribing the background tiles from Super Mario Bros. and the sprites from Super Mario 3, almost pixel for pixel out of a magazine, in attempt to find some way around the stomping issue.

Even more so than Link vs. Gannon, Jario! is barely a game. I didn’t bother to animate the sprites or design a real level; my whole concern was with trying to force an issue on which the engine wouldn’t bend. It was just as well; I never much liked Mario anyway.

So most of my tributes were a bust. That can be a problem when you have a fixed idea of what you want to do. When you follow the tides of intuition, things tend to just work. You take what comes and you look for something unusual to build on. When you’ve a specific goal and method in mind, anything can trip you up — and since that’s not where your head is you won’t be prepared to roll with the problems and compromise. As time went on I softened in my preconceptions as to what I wanted from a game, as to what a game was, and as to how to achieve that.

About thirteen years after my last Game-Maker project, I unearthed the software as part of a series for an indie game blog. I was surprised how good the design tools still were. If anything, they were more fun to use than most of the games they produced — clear, intuitive, instantly rewarding. I knew the engine’s limits, and I was curious how well it would serve to make a contemporary indie game. In my articles I had mentioned the engine’s strengths; as a test, I chose to replicate The Legend of Zelda as exactly as possible.

I ripped the original sprites and background tiles, then enlarged them by 25% in Photoshop to fit Game-Maker’s standard. It turned out that despite the difference in scale one Game-Maker screen had the same number of tiles as an NES screen — so I recreated the maps as closely as I could, block by block. I found tricks to allow Link to burn bushes and touch an Armos to bring it to life (and maybe find a secret passage). I gave the Octorocks complex behaviors and allowed the Leevers to burrow, immune to the player’s protests.

The only real problem remaining with Overworld was the counter/flag issue. I used a web of level nodes to ensure that Link would only find the wooden sword the first time into the cave, but I knew that after just a few choices the game would soon get much too complex to keep track of that way.

I stopped after filling the world map; I figured I made my point. The dimensions are different from the original Zelda overworld — taller, narrower, and a little smaller overall — so I made do, compressing some locations and expanding or moving others. I figured if I ever continued with the game I could split the overworld across two maps; maybe connect them with bridges across a river.

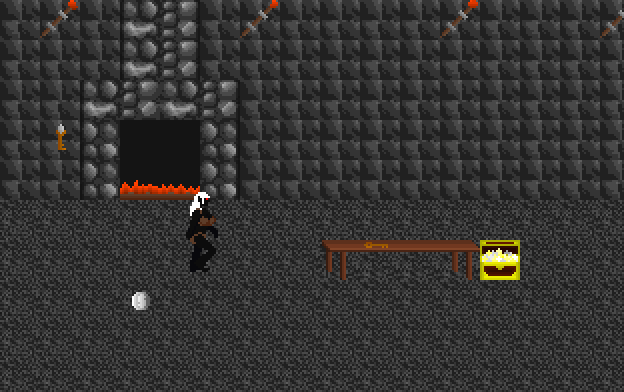

Although the game was never a serious effort, and indeed took no more than a few hours from me, my mind began to swim with the new techniques I found while bending and cajoling RSD’s engine — the screen-by-screen level design; the complex monster behaviors; the constrained color palette; multi-stage attacks; new monster birthing techniques; and in particular, using monster counter-buffers to alter the level geometry. Those techniques, and their very buggy repercussions, would become the basis for Builder, my first new Game-Maker game in half a lifetime.

Builder was a web of secrets, accessible only to a player who surrendered to and explored the engine’s glitches. A big part of the design involved ensuring that the game’s secrets remained secret until the player hit the right triggers, which on the lowest level I controlled with level nodes and paths. Finally a Game-Maker game responded meaningfully to the player’s actions, and in the most profound sense it did it behind the scenes.

Between these new tricks and my success with Builder, I was ripe with enthusiasm. It had been ages since I had worked on any game, never mind this old engine. I had the notion that I would pull out all my old unfinished Game-Maker games (nine, including Overworld) and wrap them up with style. I would put a cap on that whole thread of my life. No one would ever play them or care, but I would feel a sense of closure.

After perusing then discarding the obvious candidates (The Return of A-J, Sign of the Hedgehog 2) I turned to the best of my tributes, one that had lain neglected since 1994. RÅdïp was the unripe fruit of a competition with another Game-Maker user, a fellow whom I had met through a long distance dial-up board. Both he and I set about designing Blaster Master tributes; his was nearly as literal as Overworld, and my game took on a life of its own.

The vehicle looked similar to the one in Blaster Master, and on paper it had similar abilities — and the background tiles in the first level were similar to the tiles in one room of Blaster Master‘s final level. My vehicle controlled very differently, though — indeed better than nearly any pre-Builder character. The moves and attacks all had their own interesting flavor. The monsters were original and memorable. The level design needed work, but it involved some big, brave ideas. The game had spirit. I wondered why I ever put the game aside; it wasn’t much, but it was good.

It was also fully planned. Maybe I’d just had an Alfred Hitchcock moment and grown bored the moment I knew how the game would pan out. I had blocked the whole thing out — all of the levels, all of the bosses, the environments, the upgrade sequence, and the web connecting it all. All the game lacked was content and polish. So, slowly I added content and I polished it. Maybe I’m still doing it. I haven’t touched the game in months. Right now it just needs a final level, a transition level, and five or six bosses. I also need to complete a water level. I’d say it’s 80% done. I think I’ve just had other things on my mind.

The real trick to RÅdïp is its structure. It’s a free-roaming action-adventure; you beat bosses, earn upgrades, and revisit old areas to climb that wall or destroy that barrier with your new powers. This means affecting your environment, which means setting flags, which Game-Maker won’t abide without a headache.

Well, I survived the headache. The game has only a few items to account and maybe 18 unique areas, but it needs 80 nodes to track the changes and who knows how many links to hold it all together. If I weren’t intent on copying someone else’s idea of a game structure, I wouldn’t have bothered — but I did, and it works.

I’m building up to a point here. Hang with me.

Continuity notes:

After Nejillian Flux, The next game I designed was Explorer Jacko — you remember, the insertion game with all of the Star Control and Trek references. The ship that Jacko steals, early on? Why, the Nejillian Flux of course.

Also, some of the elements in Link vs. Gannon would later be incorporated into Linear Volume and Explorer Jacko. This is why in effect you will see Tektites bouncing around the fields of Motavia.

The story continues in Part Eight…